Long Term Athletic Development (LTAD) is a model focused on optimizing the development of talented children into elite athletes. However, what we must recognize is that the early stages of a child’s development is not determined by input from a coach or an athlete development officer. This early development is heavily influenced by the environment and the fundamental natural development and growth of the child.

When assessing this early development, it is important to look at the current state of this fundamental phase. Currently, recommendations from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the American College of Sports Medicine suggest that children up to the age of 12 partake in a minimum of one hour of physical activity per day, while screen time is limited to less than 2 hours per day. However, all of the evidence to this point is suggesting that, because of developments in modern life and digital entertainment, these recommendations are not being met. It is clear to see that the present environment is limiting the opportunities for children to obtain this broad base of fundamental movement skills required.

This poses the question – how well is nurture doing to develop what nature has endowed us with?

The Crucial Early Years

At birth, nature has provided us with a host of gifts and one of these gifts is movement. Our genetic code and our DNA prescribes our future for us. Nature has endowed us with super potential and capacity, and movement is essential in developing these gifts that nature has provided. Regular movement is not just essential in improving how well we move, it is also essential in developing our brain, cognitive awareness, personality, psycho-social skills and much, much more. Central to this development is movement in early years.

In discussions on Long Term Athletic Development, the crucial early years can often be forgotten. In reality, it is this period that develops the building blocks for a healthy and fulfilling life. Nature guides the first few months through its reflexes. This reflexive phase can last up to six months and during this phase a host of movements become refined from the primitive reflexes that nature has endowed the infant with. These primitive reflexes help to build a crucial base for the progression to rudimentary movements, then fundamental movements, and eventually athletic performance.

The rudimentary phase is the next one in the developmental journey that the infant, now child, starts. These rudimentary movements (crawling, creeping, sitting up, moving, grasping) start to take place from 6 months onwards. Indeed, these rudimentary movements are often used by therapists and coaches worldwide in developing movement control and balance even in mature athletes. They are seen by experts as key building blocks, and if they haven’t taken place produce gaps in performance.

The importance of play

As the child reaches around 3 years of age, these rudimentary movements link in with the fundamental movement patterns, with all seamlessly connected. In the early years, the child will be exposed to play related activities and movements that include these patterns, including solitary play, spectator play, parallel, associative, cooperative play.

As the child matures through to 2-4 years of age, co-operative play holds potential for development. Indeed, it would be great to see more of these playful activities across all areas of sport and embraced by sporting organisations. Different types of play contribute to a rich base of development that is not just physical but encompasses emotional, social and cognitive benefits for the child.

The net effect is that the different types of play all contribute to a rich base of development that it not just physical movement development but also emotional, social and cognitive for the growing child. In a world where sitting time and screen time is growing on a yearly basis, this important source of movement through play development is threatened more than ever and has been now for several years.

The 24 Hour Movement Initiative

In response to the growing awareness of the importance of gaining daily physical movement within the early years, an international initiative was created in 2017, called the 24 Hour Movement initiative. This initiative has gone a long way to deliver this message worldwide, and centres around 3 core recommendations:

- 180 minutes of physical activity per day.

- 10-13 Hours sleep per day.

- < 2 hrs of screen time per day.

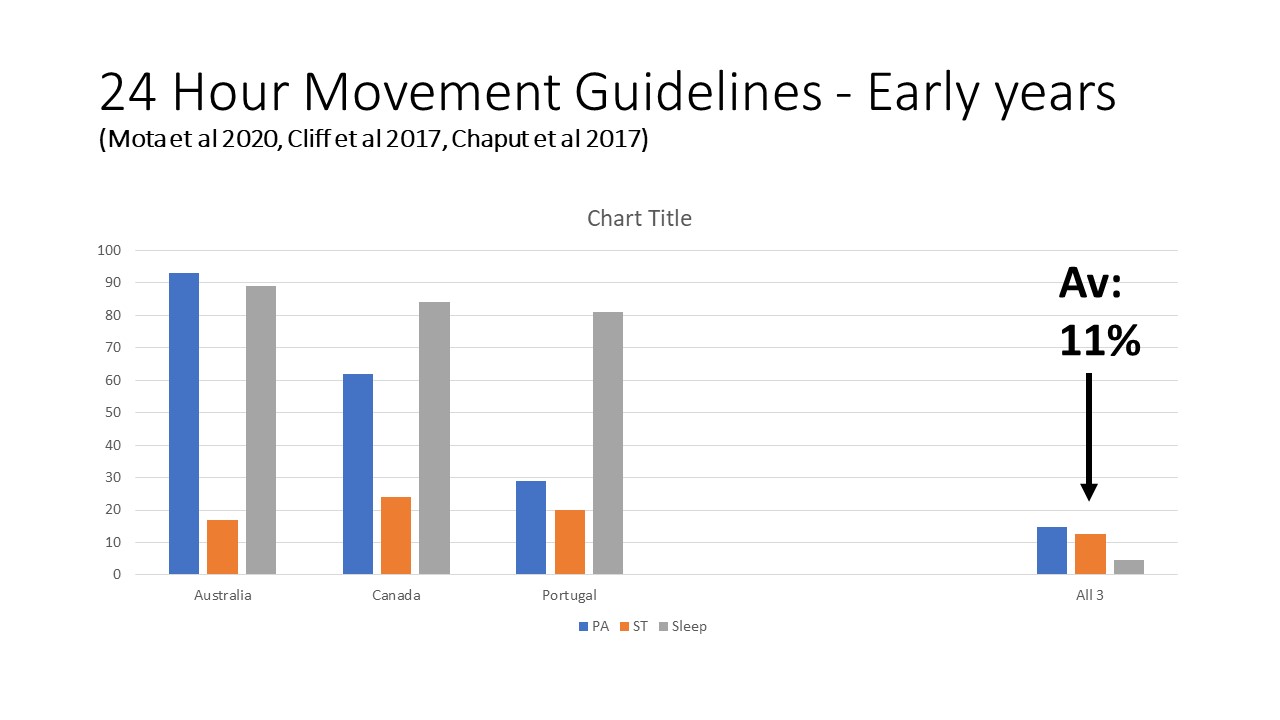

Following numerous reports and studies in recent years, it is clear that nurture and the environment in which the child grows and is meant to thrive is not doing very well. Studies from Australia, Canada and Portugal (representative of a worldwide basis) highlight the variance across the 3 activities for children under the age of 4.

Across the entire sample, only 11% meet all 3 recommendations. Screen time is where we are especially struggling, with excessive screen time associated with poor motor skills and increased physical activity in children (Felix, et al. 2020). This evidence shows that even before the age of 4, we have already exposed children to reductions in potential and capacity. This produces a knock on effect for fundamental movement skills, where we are finding a low level of competency in the majority of children.

It is of interest to note here that when we add the finding that Fundamental Movement Skills (FMS) are indeed at a low level across the majority of children within several countries, as they move from early childhood to later childhood, we can argue that nurture is not fulfilling the potential that nature has endowed.

Recent evidence from an Irish study on children between 5 and 13 years of age, shows that 78% of children scored very poor or below average FMS levels when assessed using the Test of Gross Motor Development – 2. This is broadly in line with evidence from other countries (Behan et al 2018, Hardy et al 2009, Morley et al 2015). Coupled with the findings that cardiovascular fitness has shown a decline with some stabilisation over the last 40 years suggests that the overall physical competence and fitness of children is a concern (Tomkinson et al 2017).

Interventions

The above paints a very disappointing and concerning picture with regards to early stage development. However, if we are to have a positive outlook on the situation, it is that it does not take an awful lot to improve the movement competency in children. A recent study, completed by Dr. Joe Warne and Keith Costello, found that when a simple 4 Week Fundamental Motor Skill Intervention programme is carried out, the proficiency in children’s fundamental motor skills is significantly increased.

It is clear that when children engage in a well-planned movement programme, enjoyment and skill level improves, and interventions really do work provided that they are planned well.

Our Challenges

At the moment we can confidently state that children’s development in terms of FMS and other important social, emotional and cognitive traits are not being optimised by any means. As a result, the challenges are numerous for us in relation to assisting nature to achieve its mission over the early formative years.

We can justifiably state that embracing a more balanced lifestyle within our children at a tender early age, which includes moderating screen time and promoting more physical play (that is at least moderate to moderately vigorous at times), will develop more than just movement ability, but provide a greater opportunity in developing what nature intended to bestow to the child. Now the challenge is up to the poorly performing relative – nurture. That is, the adults who oversee the nurturing environment.

Access our full webinar on Long Term Athletic Development here.

You can learn more about the courses provided by Setanta College here, or contact a member of our team below.

Leave A Comment